The Art of Andrej Troha

From the March issue of 3D World Magazine

DISRUPTIVE AND BEAUTIFULLY EDITORIAL, Andrej Troha’s work succeeds at drawing you in, with subtle details making his creations perfectly imperfect in an attempt of true realism. Whether he’s battling with soap foam or visualising secret Soviet flying machines, Troha has had a fascinating career thanks to his knowledge of science and art.

It’s clear to see the influence his scientific training has had on his 3D work, and his soft spot for fluid dynamics proved an advantage when it came to the finer points of figuring out foam. In our discussion, Troha shares some insight on his creative process and work as an art director.

What’s the aim of your art? What is it that you’re trying to achieve?

Phew, that’s the hardest question! What’s the point of my art? One is certainly improving and honing my skills. My personal projects are a way for me to learn new tools, materials, shaders and modelling techniques, and then apply that gained knowledge to my clientoriented professional projects.

There’s so much to learn and absorb with every new software update. As with most disciplines, there’s no finish line here, no now-I-know-everything feeling. It’s an ongoing process and it feels nice to be good at something, both personally and professionally.

The process typically begins with me envisioning a scenario and then attempting to construct a world based on these parameters, or at least some fragments of that world, solving any problems as I go. In the end, it’s a process of learning and discovering, and you need to do that on your own time. Clients don’t pay you to learn, they pay you to deliver.

The other goal that I have in my work is getting things out of my head; like a release valve for what’s going on in the old noggin. I’ve been on mood stabilisers called SSRIs for years now, and they have this bizarre and wonderful side effect for me: the most creative and vivid dreams. They’re visually and narratively heavy, and sometimes I feel the urge to model and render a few frames from my midnight premiere double-bill.

Exploring a realistic foam material and shader for a client

Exploring a realistic foam material and shader for a client

The everyday hammer is given a startling new twist

That’s why my portfolio has the consistency of a barf in front of a pub at 3am; no specific style. It spans from highly detailed hard surfaces to soft, abstract renders and a few pencil sketches.

What’s your balance of personal and professional work?

I’ve worked within advertising for almost 30 years now, and one thing I’ve noticed is that clients don’t care much about creativity anymore. In the 90s, creative ads were all the rage and agencies, popping up every where like daisies in summer, competed in creating fresh and memorable campaigns. Now most creative work consists of where to put a 20 per cent off sticker on a photo of bananas. The need for creativity is all but gone, so most of the creatives in the ad industry also need something to vent out ideas that are bubbling away in their heads.

Still, there’s plenty of demand for very specific realistic visualisation, spanning from package designs through to living spaces. My agency, for example, has a long relationship with one of Europe’s best sailboat manufacturers, and visualising their design ideas is really rewarding and challenging at the same time. It’s a very, very specific market and it isn’t for the faint-hearted. In actuality, both personal and professional work are frequently intertwined. It’s hard to draw a line, especially if you work from home like I do. And that’s a blessing, just to be clear.

Your work struck me as being very editorial, what was your creative journey like to get you to this level? Did you study at university, were you self-taught, or perhaps a mixture of both?

I have two almost completely opposite formal training degrees. The first was a BSc in chemical engineering from the University of Ljubljana’s Faculty of Chemistry and Chemical Technolog y, that gave me the hardcore, no nonsenseoriented take on the world and society. The other degree is a BA in visual communications from the University of Ljubljana’s Academy of Fine Arts and Design, which gave me classical art training.

You could say that my five-yearlong chemical experiment was a waste of time, but there’s a lot of natural science involved in 3D, from mathematics and physics to chemistry and even biolog y. It’s good to know some things about light transport, colour mixing, fluid dynamics and rigid bodies.

Exploring the volumetric materials, light and controlled chaos of Cinema 4D’s MoGraph toolset

A different take on Mercedes’ Unimog vehicle line

Silverware improved for your inconvenience. One of the projects where I tried to master Cinema 4D’s long-forgotten physical renderer. Maxon abandoned this renderer and switched to Redshift not long after

Both educations gave me a solid base to build on. From there it was up to me. You can’t expect formal education to prepare you for the reality that’s out there, you need to educate yourself and keep that thirst for knowledge alive and kicking. Maybe it’s that chemical engineer in me that wants to keep exploring, and I love how every single project, be it professional or personal, opens hundreds of new challenges. Every answer has hundreds of new unknowns. And that’s the most thrilling and exhilarating thing.

The first piece of yours I saw really caught my eye, which was the capillaries and foam. The detail and reflections in the foam are impressive. What was the inspiration behind this? Was the foam hard to render?

A client of ours asked us to deliver a very specific visual of a soap bar with dynamic foam. First, we tried out a classic approach and photog raphed the thing. As you can g uess, it didn’t go as planned with bubbles acting erratically and bursting in the lens at an alarmingly fast rate.

My soft spot at uni was fluid dynamics, so I promptly suggested trying this in 3D. I have quite a few bubble shaders under my belt – beer, memory foam and so on – so I was sure it would be a walk in the park. Well, it was, but the park was ridden with deranged zombies and crazed pit bulls.

Contrary to beer foam, soap foam is uneven, and the bubbles are randomly positioned, shaped and sized. Soap foam bubbles interact much more with each other than in beer for example, where bubbles are much smaller, more or less the same size, and practically rigid.

It was immediately clear that I wouldn’t get away with shaders only, so I resorted to a fresh and very capable soft-body simulation engine in Cinema 4D; specifically Balloon Solver. I split the workflow into two parts: bubbles and space between bubbles. I then created a simple material for each of them, and used Cinema 4D’s Volume Builder to soften things up. I created some test renders, and the client was happy, so we went ahead and created the key visual.

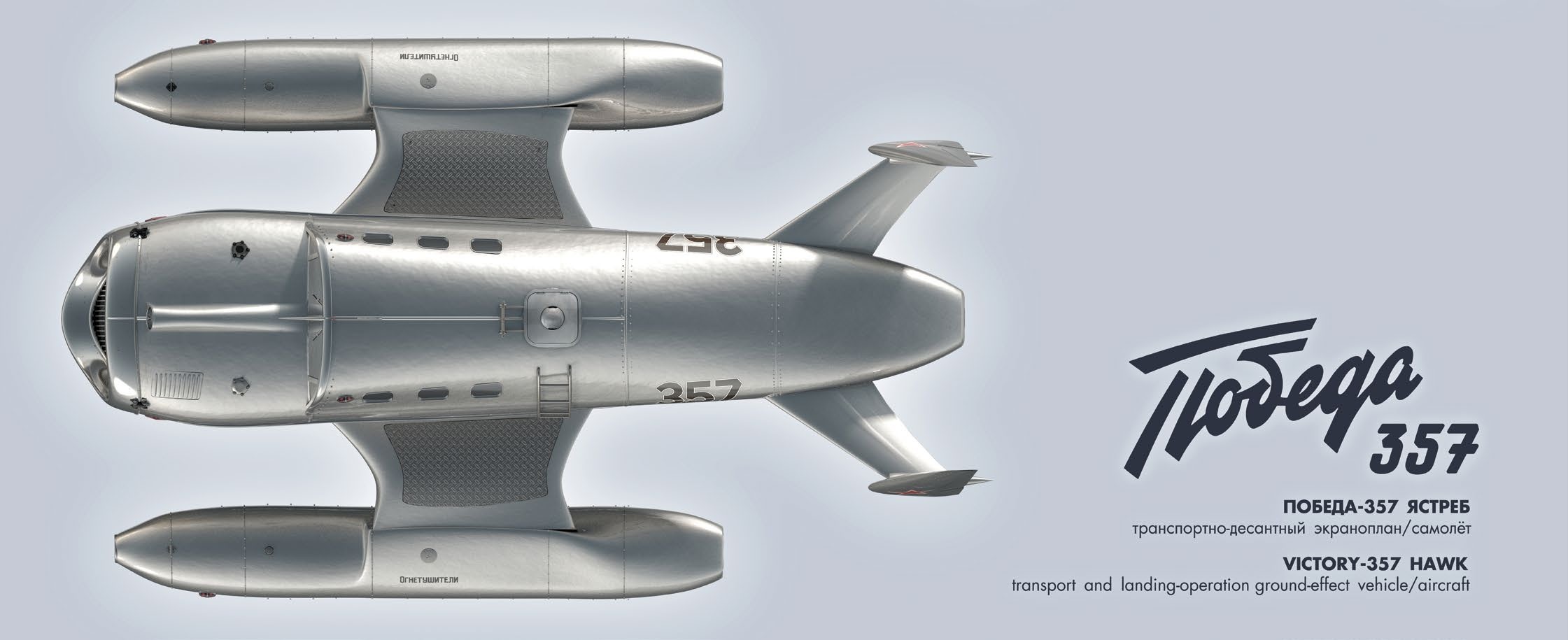

The Pobeda 357 was produced as a model kit

The Pobeda 357 was produced as a model kit

Where do you get inspiration? Are there artists that have been particularly inspiring for you?

A slight tangent if I may. I have this rather unpopular opinion about what art is. Let’s take Michelangelo’s David for example. What’s new in his work? Nothing. Nothing at all. We see David exactly as the Old Testament describes him: slightly frightened but determined before the battle with Goliath. Is he anatomically perfect? Of course. Are the veins in his arm swollen? Yep. Is he standing in the ideal contrapposto? You bet. All that’s true, but it’s just a commissioned, finely crafted statue. There’s nothing disruptive, it’s just a very, very nice statue.

For me, the mission of art is to move us out of our comfort zones, to ask us questions, to draw our attention to the problems of society, science and so on. Art must have a social meaning, just being beautiful isn’t enough. Banksy’s work, for example, is technically, deliberately naive. The production value is close to zero, but they’re as disruptive as few contemporary works. I love disruptive artists, from the simplicity of Kazimir Malevich and Edward Hopper to the total mess of Zdzisław Beksinski, ´ the uneasiness of Uno Moralez, and the meatiness of Mark Powell’s dioramas.

You have a great variation of themes in your work. What has been your favourite project?

I’m a huge dieselpunk fan and basically in love with the post-World War II period until 1960, mostly due to the optimism, technological achievements, and unadulterated trust in science. That obsession of mine caught the eye of one of the largest model kit manufacturers.

So, back in 2018 they reached out to me to create the concept for their new line of experimental models. More specifically, secret Soviet projects that are so out of this world that they would look credible. I came up with this beast of a flying machine called Pobeda (Victory) 357. It was a jetpowered ekranoplan that could also fly due to the implementation of an anti-gravity system that was developed by a fictitious gravity control propulsion research centre in Moscow, and powered by enormous 15,500 hp Kuznetsov NK-12 engines. There’s a much longer back story that was there to sell the narrative.

A magazine cover from the 1990s

The manufacturer was absolutely ecstatic and it went into production more or less immediately. The tricky part was how to convert the Cinema 4D model into something they can use to make tools for injection moulding. My answer to that was a resounding ‘I don’t know’. But the model maker’s tool shop’s more talented team found a way, and Pobeda was on the shelves within a few months.

From start to finish, the project was pure fun, and one of the few commissioned projects where I had complete control. Oh, and why 357? Because the numbers look fantastic with their retro Soviet aesthetics.

How many years of experience do you have? What skills enable you to reach this high standard?

I started off working in 3D back in the early 1990s with Imagine, Cinema 4D and LightWave 3D, all on Commodore Amiga. In 1993 we started a gaming magazine and I was tasked with creating covers, which were famous for having absolutely no connection with any of the issue’s themes. Maybe it’s this total creative freedom that follows me throughout my career that has enabled me to be what I am. An enormous privilege.

What have been the hardest details to master? How have you overcome these challenges?

Something I like to call organicity. Just the right amount of wear, subtle signs of usage, organic translucency, and happy little accidents, as Bob Ross would put it; things that enhance the realism of a picture. Sometimes I see renders that are amazing but just too clinical. Sometimes there are just too many scratches, dents and curvature wear on objects.

Fun with Redshift and Cinema 4D’s Volume Shader and Volume Mesher

You need to subconsciously absorb that organicity, but not notice it to the level of dominance and obtrusiveness. If you observe the world around you, nothing is perfect; there’s always something amiss. A bottle has air bubbles in the glass, or a chair’s legs might be slightly misaligned.

I just try to observe where the spoon is most worn, how brutally unsymmetrical faces are, and study how light scatters through a leaf. Observing the world around me helped me a lot. With all that said, finding the right balance of cleanliness and grunginess is the hardest for me to learn, and I’m still far from mastering that.

What advice do you have for new artists eager to produce work as good as yours?

I know it might sound cliche, but try thinking outside the box. Try thinking about things and concepts nobody has ever thought about, imagine worlds that have never been created. Be creative in using available tools too. You can, for example, use Cinema 4D’s Pyro to create amazingly realistic snow-covered objects. Use your imagination, be observant of the world around you, sketch before you fire up your 3D software, and last but not least, my most Miss World/Taylor Swift advice is just to be yourself.

In your time as a 3D artist so far, what has been your greatest achievement?

Probably working with 3 Arts Entertainment on a US TV series called Baskets. I was tasked with creating a dieselpunk-ish set for a few of the episodes. Working with Hollywood is a special experience; it’s fast-paced no-BS on one hand and total creative freedom on the other. Sadly Louis C.K., one of the co-creators of the series, did what he did, and the FX network shut the whole thing down.

Oh, and being featured in one of the leading 3D magazines isn’t something to scoff about either!

Contact

Let's create something amazing together

Agencija Klicaj, d.o.o.

Dolenja vas pri Polhovem Gradcu 22, 1355 Polhov Gradec

VAT: SI72363355

info@klicaj.si